Good day friends.

I could hardly believe my luck when I got hold of a Hester Bateman tablespoon the other day. Length: 21.6 cm. The pics will show.

Year assayed: 1784. Lion passant guardant. I have some questions, please.

Firstly, if the maker’s mark was put on the spoon after assay, why would the mark be put on upside down? Surely, a discerning customer might see it as a detracting “fault”?

Secondly, if one looks carefully at the bowl, inside & out, a large number of very fine and quite regular hammer marks are seen and felt. Might this merely indicate a product of silversmithing from the 1700’s, when machinery and presses had not yet been brought in? Or might it be a later effort to reform a dented bowl?

Lastly, I am at a loss concerning the heraldic crest. I browsed through the online Fairbairn Book of Crests but could not find a crest even vaguely similar to the ons on the spoon. Could someone help with this mystery, please?

Regards

Jan.

Firstly, if the maker’s mark was put on the spoon after assay, why would the mark be put on upside down? Surely, a discerning customer might see it as a detracting “fault”?

Look at the header image on this forum page. Not even Paul Storr seems to have been concerned about that! ![]()

I can’t argue with that logic, Jeff! ![]()

Regards

Jan.

Makers’ marks were applied before being sent to the assay office - there could then be no argument over whose silver was found to be sub-standard. I guess some of those responsible for adding the hallmark had a peculiar sense of humour!

The Batemans were noted as early adopters of machinery for silver production, consequently reducing the amount hammering necessary, and then for good quality control of the final product so I suspect that the marks on your spoon are the result of later damage.

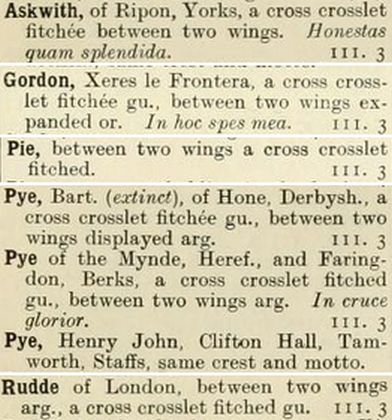

In the 1905 edition of Fairbairn’s Crests the following crest, which seems to have the same heraldic make-up as yours (a cross crosslet fitchée between two wings), is attributed to family names: Askwith, Gordon, Pie, Pye and Rudde.

I’m not sure what colour the hatching on the wings represents; squares normally means sable (black) but I think the squares are normally smaller. In any case the only wing colours mentioned are or (yellow) and arg[ent] (white).

Thank you so much, Phil! You are very helpful with your kind efforts to advise and I really appreciate it! I always follow up on your comments (not forgetting other collectors who also help out when they can) and I’m gaining understanding about silver flatware as I go along. Thanks again!

Regards

Jan

Good day, Jan. You have indeed got a fine example of Bateman flatware with an interesting crest.

Thank you for sharing with the rest of us.

Hester took over the business from her husband, a buckle maker as I recall, and by investing in modern machinery for the day, specifically a rolling mill, managed to achieve three things rather quickly:

First she and later her family managed to reduce the cost of production by about half, secondly she managed to reduce the amount of raw materials in any given item by up to a third and lastly she cemented herself a position as a leading lady silversmith and created for the collector a premium brand.

The Bateman name was carried on through four generations and they used every device in the book and a few not really in any book to stay competitive. One of them, and if you are going to start collecting Bateman you might want to look out for it, was to dodge the sixpence in the pound duty imposed on silver to help defray the cost of the lost war against us over here. You call it the American Revolution. The dodge was to ship shop product to the Channel Islands where the tax was less then import it back with no tax due.

Philippa Glanville’s excellent work on lady silversmiths provides a useful synoptic of the skills they all brought;

The first thing the readers notices is there are rather a lot of women whose diamond mark indicates they have taken over a dead husband’s business. The second is there are a lot of dead husbands.

The death rate among silversmiths is very high indeed if they are working in the the shop. It got especially bad when the lost mercury system of guilding took over. Mercury inhalation not being helpful. We know Solomon Hougham’s brother, Charles died of exactly that.

Most of the ladies upon the death of their husband did exactly what they had always done, balanced the books and looked after the customers while making sure the journeymen and tally men were paid and not stealing or cheating. They employed foreman to do the supervision in the shops and set about to expand the business. Mistress Bateman, whose illiteracy is exaggerated to make the point, excelled at this.

Bateman silver collectable or not? Yes, but don’t give up on her sisters in business they are fun too. A few you see up regularly are Mary Chawner, the daughter sister and wife of silversmiths whose work is some of the best on offer in a time when silver was becoming plentiful and items heavier, Anne Tanqueray (1691-1733). Subordinate goldsmith to George 1st and probably the best woman silversmith of all time and an ancestor of mine, Elizabeth Eaton, again wife and daughter of silversmiths, nothing special just her stuff is everywhere and always excellent. Lot of overstamping into the Channel Islands, Simon Pantin’s daughter Elizabeth Godfrey, probably the best silversmith of her day regardless of sex and so on. If I am giving the impression they were few, that is false there were hundreds of them often working under their husbands mark. Ireland too had many. Jane Williams of Cork springs to mind.

Talented hardworking and business minded. They were feminists of necessity, they were mothers and daughters and all that meant in a patriarchal world.

CRWW

CRWW, thank you very much indeed for this very readable post. I’m sure many forum readers will join me in voicing my gratitude. I’m happy to say I do actually have an Elizabeth Eaton! I wanted to have a set of spoons by Samuel Eaton before her, but the owner was not able to relinquish his tight grip on the set! ![]()

Regards

Jan

You’ve done lot of useful work on this talented family originally out of Northamptonshire.

.

I’m thankful, Guildhall. But your own contribution has been even greater.

I am still searching for clues as to exactly when Hester Bateman began using machines to help manufacture her wares, thereby allowing her and her workmen to move away from hammerwork.

And then there’s the matter of Elizabeth Eaton, another of the lady silversmiths, about which you mentioned higher up in this topic that she was an ancestor of yours. She was the wife of William Eaton II, born 1788. He was the son of William Eaton I, who first entered his mark in 1781, and died in 1845.

Now who were this William Eaton I’s ancestors? Was Samuel Eaton one of them? In 1745 Samuel Eaton was already known as a eminent silversmith. (His father George was a farmer.) Samuel died in 1767. One of Samuel’s brothers had a son, John, who became apprenticed to Samuel in 1738. This John became a silversmith and worked as such between 1745 to 1767. (John had a brother Thomas, who, although it is known that he made spoons, did not register a mark.)

Now, the question is, can we connect Samuel Eaton with Elizabeth Eaton? In other words, might Elizabeth’s father-in-law, William I, have been the son of Samuel Eaton, or perhaps the son of Samuel’s nephew John?

Guildhall, have you done some genealogical research concerning these ancestors of yours?

Regards

Jan

So the question is when did the Batemans get into the rolling mill business and where was that mill operating and how was it financed and by whom?

Here’s what we know:

“From 1774 onward Hester Bateman began purchasing pre-prepared lightweight units of sheet silver from the Birmingham manufacturer Boulton & Fothergill, and focused on assembling, decorating and finishing works for sale.The production of such silver units reflected advances in manufacturing such as the introduction of… rolling machines to achieve much thinner gauge sheet silver than had been previously possible. It also reflected the emergence of… low-level mass production, which enabled Bateman and others to compete successfully with the newly emerging trade in Sheffield plate.”

(Hester Bateman: An eighteenth-century entrepreneur | NGV)

So they bought rolled silver from Boulton’s Birmingham manufactory, but did they eventually invest in their own equipment to roll their own ingots into sheets?

And if they didn’t, it would have had to have been something else other than access to sheet metal and its use in the flatware and hollow ware business that gave the Batemans’ primacy.

The Bateman premises size at 107 Bunhill Row may give us a clue. The entire operation was confined to a single floor on a very tight lot and the benches and furnaces contained therein used, according to contemporary accounts, all of the space.

"With the help of her family of five children and apprentice John Linney, Bateman registered her mark in 1761. Her workshop produced thousands of pieces until her 1790 retirement. Her descendants ensured the workshop continue to thrive through the mid-19th century.

“The key to Bateman’s success may well have been the integration of modern technology with classical design, which attracted a solid middle-class market. Using cost-efficient manufacturing processes, the workshop produced domestic items—coffee pots, tea urns, cruets, teapots, salvers, goblets, salts, sugar tongs, and flatware, Bateman’s specialty. Using easily worked sheet silver from Birmingham, the Bateman workshop decorated items with simple yet elegant patterns, such as a thin, precise line of beading or bright-cut engraving.”

If the family was to have invested in a rolling mill, they would have needed to borrow the capital – deceased husband’s buckle making business produced adequate revenue to support the family of seven, but allowed little margin for accumulated capital. To have borrowed she would have needed to put up assets. Aside from the shop and its production she had none. And prior to the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act it was tricky to lend to females as if they remarried any property of theirs, even if subject to a chattel mortgage or other lien, became that of their new husband.

So let’s look at where we know she did obtain stock of raw silver.

In 1761 Edward Rushton, who six years earlier had leased property on Hockley Brook near Birmingham, sold his interest in it and a rolling mill powered by the brook he had built to Boulton and Fotheringill. They ran the water-powered mill to create sheets of silver and other malleable metals for the toy manufacturer, Matthew Boulton. (He never was trained as a silversmith despite his massive contribution, his registered mark and his successful lobbying to get an assay office in Birmingham so he didn’t have to ship wares to Chester.)

The water powered mill was replaced 20 years later with a steam powered mill and mint.

There is no evidence that a plant of this size was ever located at 107 Bunhill Row. It simply could not have accommodated it.

So it looks as though the waters of Hockley brook, responsible for so much of the genesis of Birmingham manufactory, produced Bateman silver sheets from 1774 to 1782 when steampower took over from stream power.

If the Batemans had invested in a similar plant somewhere else that would have been a matter of record. There is none.

There is, however, considerable evidence of the Bateman family duty dodging and employing other perfectly legal but, by standards today, sharp practice to keep themselves on top. A great deal of their product was shipped to the Channel Islands and then back to the UK or directly to the Americas duty free or at the reduced excise of 1.5 pennies instead of sixpence.

(An early recorded use of the Channel Islands as an offshore tax haven.)

Recently I came across a William Bateman ladle with the king’s head (duty paid mark) erased by “searchers” or “waiters” (two customs officers functionaries) at port of departure in a box of Federal silver in New York.

Prior to 1787 there were over 1,200 separate UK excise tariffs. An act of parliament passed that year cut this to something manageable but silver remained subject to duty until the end of Victoria’s reign and the sovereign’s head remained showing duty paid.

That the Bateman family, born of a parent who was allegedly illiterate, had this dogged determination to thread their way through the morass of sometimes conflicting law on duty payable, demonstrates a family assiduousness which might, in and of itself, explain its success.

Christopher Wilson

Guildhall Antiques

Toronto

Christopher, this is a marvelous effort on your part to share knowledge with us. I’m sure we are all much obliged! This contribution needs to be re-read and contemplated.

The only extra comment I might make at this stage is that in Hester’s time at least, they did not have the use of their own rolling mill (as you have said), nor also of stamping dies (I assume) to press out the shapes of their flatware. They would then only have had shaped anvils and hand-held hammers.

Regards

Jan