Good day, friends.

I have acquired a sterling silver cauldron salt cellar with London assay mark, and Gothic year letter ‘k’ for 1845, but I am struggling with the maker’s mark, as it is nearly obliterated. Also, the bottom of each foot is monogrammed, but I don’t know what the letters could stand for.

All that I can discern of the maker’s mark is the G with a dot. The only maker I can find with a mark beginning like that, is George Ivory. What is your kind opinion?

Regards

Jan

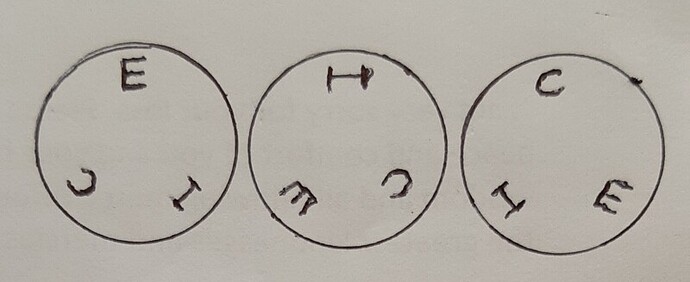

You will see a single letter on the bottom of each of the feet. I make out an E, an I and a C. I can only guess as to the purpose of these letters: either the initials (monogram) of the cellar’s first owner, or perhaps three journeymen’s marks. Please offer your opinions on this.

Thank you

Jan

I’m pretty sure that the initials on the feet are marriage initials. We normally see these on spoons and they take a triangular form with the top letter the groom’s surname initial and the other 2 the bride’s and groom’s first name initials. There is no obvious order on these feet.

The date of this salt is actually 1765 - note the crowned leopard’s head not used after 1821 and the lack of a duty mark. This date quite obviously rules out George Ivory but I can’t suggest who it could be.

Phil

Phil and others reading here, what a total chump I am for missing those details! I was concentrating too hard on deciphering the unclear maker’s mark, it seems. No excuse! Thank you, Phil, for waking me up.

I’m continuing the search for that elusive maker, and I’ll gladly report back.

Regards

Jan

I have spent a little more than an hour doing what is so very exhilarating for me and probably all dedicated collectors, which is doing ‘research’ on antique silver and finding clues and following them up to make acceptable findings! I have found, without a shred of doubt from my side, that the maker of the salt cellar is John Faux & George Love. The mark is I.F over G.L. On my salt the only letter remaining is the G, with just the faintest shadow of the L if you look very very hard.

Faux went into partnership with Love in 1764. That fits in nicely with my salt’s year letter indicating 1765.

This is all thanks to you, Phil!

Jan

Secondly, I got to thinking about what you wrote about the letters on the bottoms of the feet, being marriage initials. You said there’s no obvious order on these feet. I thought so too, but then something clicked: it all depends how you look at the letters. If you turn the salt with the E uppermost, the C and the I are slanted, so that one cannot easily read them. If the I is uppermost, all three letters are lying on their sides. Only if the C is uppermost are the I and E easily readable.

So, if you agree this theory holds water, then the groom’s surname initial is C and the bride’s and groom’s first initials are I and E. Please see the pic. I hope you agree.

Regards

Jan

Thank you for sharing your cauldron salt with us. These “lost registry” marks are a constant challenge. The only thing it reminds us of if the modern problems with your Parliament aren’t all that modern.

THe only mark I can find for the Faux/Love partnership are these:

https://www.925-1000.com/bx_iFauxGL_L.html

Your mark appears to be in a curved punch and I am not certain there was ever another mark or double mark above the G. .

But as always you would have the advantage over anyone reliant only upon photos.

So what did the partnership make: From these marks it looks as if sugar nips and tongs were the thing. Salts, because by the 1760’s were a mass production market with people like the Hennells and the Muns occupying the field, generally others steered clear. There is some overstamp work and it is certainly possible for smiths to acquire salt sets off the mass production shops and stamp them as their own for assay purposes.

Like Phil I do not have an alternative to the Faux/Love partnership. A quick scan through Jacksons and Phil’s own fine compendium leaves a couple of possibles but nothing that I’d bet the house on.

The ownership marks stamped where nobody would think to look rather than being proudly displayed as a scripted initial smashup or crest on the side only makes sense when you delve into the deeply paranoid English middle class about the time your mad King was about to impose the Stamp Act taxation on us in North America and screw things up for everyone for a century. Georgian wives were a possession with no independent right to own property and silver was an expensive commodity before the 19th century mines in this country flooded the market. Swiping a chap’s wife was fairly heavily sanctioned but swiping his salts was a capital offence and nothing gave the Georgians more pleasure than string up a servant or two at Tyburn before lunch. So these marks were for identification of ownership and a snare for the light fingered rather than an assertion of wealth.

Now all you have to do is find three more similar salts to make a harlequin set of four. Each diner would have had one of these within reach and stuck his meat in it. Salt spoons which were being invented about then were a superfluity. Remember salt too had its challenges before it was chemically modified not to stick together.

Bonne chasse,

Christopher,

St Marten

Given your theory about the initials is correct, and I think it is, then your salt may have been the property of John and Elizabeth Chalfont. The Chalfonts were a prominent Sussex family who owned a plantation in Delaware and were slave owners. You didn’t say where you acquired your salt but about this time a great deal of English silver was being shipped over here, along with clock mechanisms. Within a decade the import market was closed off by the War of Independence, the harrying of British merchant ships and slavers by American privateers and the rise of our own manufactory. I stress this is pure conjecture on my part. Any sign of a rubbed out crest or initials on the side? A flexibility of the metal will indicate.

CRWW

Christopher, I thank you for offering such a broad and stimulating discussion on my salt cauldron. I had earlier thought Phil to be probably the only lit candle in the room, but I now see the room has some other candles burning equally bright, too!. Your kind thoughts have been read thoroughly by me.

It is true that the “I” initial can also be read as “J” (as also in the case of “I F”, which reads “John Faux”), so according to your conjecture “C” might stand for Chalfont, “I” for John and “E” for Elizabeth. Why not?

However, I am not in England, I am in South Africa, and I got this salt from an antique shop in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape. Now, following your conjecture, the salt was made in London in 1765 for the Sussex family Chalfont, and after their marriage somehow arrived in South Africa either directly or via Delaware in the US. I know we’re only having fun here, trying to put things together, but if this is what actually happened we will never know. But I love it when we exchange thoughts like this and I am indebted to you, Christopher.

Regards

Jan

You might be in a better position than I to determine the African settlement of Chalfonts if any. They certainly came over here and did well. Phil is an incredible source of data on silver marks and I constantly learn from his excellent site.

Christopher

Christopher, such determination of the African settlement of the Chalfont family is something I should get to as soon as time allows. I trust the coming of the new year opens new opportunities.

Thank you.

Jan